Adri Boon translated poems by Roberto Piva, Horácio Costa and Ismar Tirelli Neto into Dutch for Samplekanon to accompany this essay. Here you can read a Dutch translation of this essay by Jetske Brouwer.

1.

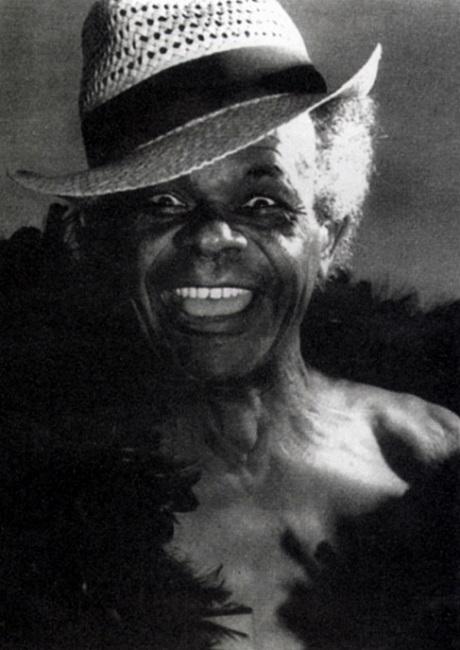

When I look back at my childhood in Brazil in the early 1980s, I am often taken aback by the strange dualities in the society that surrouned me then. Born in 1977 during the government of Ernesto Geisel, one of the generals that led the Brazilian Military Dictatorship (1964-1985) and rotated every 4 years with other generals to keep up the appearances of a democracy, I was confronted early on by the images of homosexuals on television despite the conservative moral stance of the regime. One such figure was singer Ney Matogrosso (b. 1941). After a successful career with the band Secos & Molhados – which defied moral codes in the mid 1970s at the height of the dictatorship – he was a constant guest on music shows.

Even more blatant in his defiant mannerisms was Clodovil Hernandes (1937–2009), a former fashion designer turned host to one of the most popular late night interview programs in the 1980s. Clodovil, as he was known, was an openly out gay man, every night on television, often leading my father to yell homophobic remarks between laughters at his jokes. And I could not not mention Roberta Close, a transexual performer and model, a constant guest on television, Playboy bunny, and possibly one of the strongest challenges to Brazilian notions of masculinity in those years. The desired danger, the hushed desire for her. And yet I remember quite clearly how she seemed to cause no awkwardness in the living room when she appeared on the screen. Yes, it always mentioned “she was a he”, but it would often be followed by the sentence “mas é linda” [but she is so beautiful], always with the feminine pronoun.

But this is the deceptive openness of a country which is deeply conservative and violent if often self-indulgent. Around those same years, as Rita Moreira discusses in her documentary ‘Hunting Season’, homosexuals were murdered indiscriminately in the largest city in Brazil, São Paulo. It is chilling to watch some of the interviews with citizens who openly say on camera that “this is what homosexuals deserve.” Paradoxically, though homosexuality was truly never criminalized by law in the country, it was only removed from the charter of psychological disorders in the 1990s.

2.

In one of the first attempts to map alternative sexualities outside the Western heterosexual norm in the territory now known as Brazil, João Silvério Trevisan revisited the surviving documents from travelers, missionaries and colonists to attempt a picture of Amerindian sexual practices before the Portuguese Invasion of 1500. It is a monumental or nearly impossible task, five centuries later. The title of his seminal work, Devassos no Paraíso [‘Perverts in Paradise’, 1986], comes from a quote by conservative historian Abelardo Romero (1907–1979), who used such words to describe Amerindians and their sexual liberties before the Christian invasion. The information is sparse. Trevisan quotes a German traveler captured by the Tupinambá tribe, Hans Staden (1525–1576), who wrote of enemies vanquished in battle given the right to sleep with both wife and daughter of the conquering tribe’s chief before being put to death.

Other travelers wrote of the openness with which the Amerindians enjoyed discussing their sexual escapades, their polygamy and polyandry, or how jealosy seemed to be inexistent among the known tribes. But of all practices which shocked those first Christians in the Tropics, none attracted as much religious fervor and wrath as the one we now call homosexuality, though in those days they prefered Latin words, that is, the peccatum nefandum. The only accounts we have are those given by European Christians, and only through them can we try to imagine what a myriad of moral codes may have existed within the hundreds of different tribes living in the territory before the year 1500.

Famous in Brazilian History, Portuguese jesuit priest Manuel da Nóbrega (1517–1570), first Provincial of the Society of Jesus in colonial Brazil, wrote however of how the Amerindian moral codes had actually first subjugated those of the Christian invaders. In one of his letters, he comments on how many Portuguese men had taken Amerindian men for wives, “following the custom of the land.” About the Tupinambá nation, he wrote: “They are very fond of the peccatum nefandum, among whom it is not counted as an offense; and the one who considers himself a male boasts of his pride in such conquests, naming this bestiality as prowess; and in their tribes through the wilderness there are some men who lie in public houses for all those who may want them as public women.” Pero de Gândavo would write in 1576 that the Amerindians “gave themselves to the obscenity of sodomy as if deprived of male reason”, and he is also the writer who would first describe specifically lesbian relationships among the Tupinambá: Amerindian women who refused marriage with men, and took instead “women for husbands, doing with them all that has been reserved for men and women”. Among the Guaicurus there were socially accpeted members known as “cudinas”, castrated men who dressed and lived as females, and among the Bororos young males practice sex in the “house-of-men”, forbidden for women.

This clash between Amerindian and European mores would continue down the centuries, later made even more complex by the arrival of millions of kidnapped men and women from Africa to serve as slaves. This violence, however, was not always simply reserved to vocabulary and narrative style. One of the most famous cases was that of a Tupinambá man called Tibira, accused of sodomy and executed savagely by being tied to the mouth of a firing cannon in 1614, by orders of French missionary Yves d’Évreux (1577-1632), of the Order of Friars Minor Capuchin.

3.

This long preamble before dealing with the work of queer poets in Brazil is necessary to contextualize in which conflicted and sexually ambiguous and complex society such poetry takes place. Before openly homosexual authors such as Lúcio Cardoso (1912-1968) or Roberto Piva (1937-2010) would come to light, homosexuality had been approached in Brazilian literature, but in a more oblique manner and always surrounded by scandal. In 1888, remarkable author Raul Pompeia (1863–1895) published in Rio de Janeiro the novel The Atheneum, describing in a seminal way how sexuality and violence were intertwined in Brazilian society, setting his novel in a boarding school of the elite. But his intention was satire, a critique of upper class Brazilian society in the early years of the Republic, still attached to monarchist privileges and decadence. And he himself would come to commit suicide – “to defend his honor” – after finding himself embroiled in a polemic with poet Olavo Bilac, who had “accused” Pompeia of homosexuality in their exchange of seething articles through the Rio de Janeiro press due to their political disagreement surrounding the government of Floriano Peixoto. This was the same time, it is important to note, in which Oscar Wilde and Lord Alfred Douglas found themselves caught up in the catastrophic trial that led to Wilde’s imprisonment and early death.

Other authors who are noteworthy are João do Rio (1881-1921), our Wilde-like dandy and first to accept and play with the boisterous rumors surrounding his ambiguous looks; Mário de Andrade (1890–1945), founding member of the Modernist movement and an extremely private man whose homosexuality would only be attested in 2015, 70 years after his death when his work became public domain, and yet only after a legal battle for the release of one infamous 1928 letter in which he elegantly tries to find a way to discuss the matter with fellow Modernist poet Manuel Bandeira; and finally Lúcio Cardoso (1912–1968), close friend and confidant of Clarice Lispector, author of openly homoerotic poems and one of the starkest critics of Brazilian sexual hypocrisy in his novel Crônica da Casa Assassinada [Chronicle of the Murdered House, 1959]. In the 1960s however, commercial success would come in no uncertain terms to a lesbian writer, Cassandra Rios, one of the first women to write in explicit ways about lesbian desire, reaching the top of bestseller lists, though she would never receive critical acclaim as some of her male counterparts.

4.

But if Brazil witnessed ferocious repression during the 1960s and 1970s in the hands of a Military Dictatorship, the dam had been broken. The artists surrounding the Tropicalist Movement had begun work that would challenge the national esthetics and morals, especially in the figure of an androgynous Caetano Veloso.

The 1970s would see an explosion of activism and courage, with writers such as Caio Fernando Abreu, Silviano Santiago, Marize Castro, Renata Pallottini, and others. But I have chosen three specific poets for this article, trying to span 3 different generations. These poets are Roberto Piva (1937–2010), Horácio Costa (b. 1954) and Ismar Tirelli Neto (b. 1985). It is one frame of a much larger picture, and any approach to contemporary queer-bodied Brazilian poetry will need to go through the works of lesbian writers such as Angélica Freitas and Tatiana Pequeno, or trans poets such as Tom Nóbrega, something I hope to do in the future, though I have written about some of them individually elsewhere.

Roberto Piva has achieved iconic status in Brazil today, but it was not always so. His début in 1963 [Paranoia] was hailed as the continuation of a Surrealist tradition by none other than André Breton, and Piva would be among the first Brazilians to discuss Beatnik poets such as Allen Ginsberg in the country, but his arrival was badly timed for the main and noisiest debates in Brazilian poetry at the time. The 1950s had seen the arrival of a diverse group of experimental movements such as Concrete Poetry, Neoconcrete Poetry, Praxis Poetry and Process Poem, all of which were anchored within the constructivist forces of International Modernism. Roberto Piva’s visions and hallucinations in a metropolis like São Paulo seemed untimely in the same city that was up-at-arms discussing the graphic experimentations of Augusto de Campos and Décio Pignatari, only a few years older than him. And in a largely agnostic environment, Piva’s paganism and calls for a return to the shamanic forces of the word seemed even more out of time, if not out of place. He would go on to publish his visionary books throughout the 1960s–80s, but as a critic once wrote, his one-man-ongoing-revolution found few followers, though he was a cult figure in the undergrounds of the city. This only began to change in the early 21st century, when after a few decades of rational, constructivist and formalist poetics, Brazilian readers started looking for the madmen and madwomen among such sane writers. This would then be the time of Roberto Piva, as it was for another carnal mystic, Hilda Hilst. Sadly, it came too late. Roberto Piva died in São Paulo on July 3rd, 2010, as his collected works were being prepared for publication.

Now in his 60s, Horácio Costa lived many years outside Brazil, teaching literature in Mexico. In a pre-internet age, this was enough to exile not only the body that produces the poetry, but the poetry itself. His début came in 1981 with the volume ’26 Poems and 8 Stories’, but it was the columes ‘Satori’ (1989) and ‘Quadragésimo’ (1999) that established him among poetry lovers as one of the most sophisticated voices of his generation. Since his return to Brazil where he is now a professor, he has also been instrumental as a teacher to younger generations from his classrooms in universities. As a poet, alongside novelist and critic Silviano Santiago, one could claim him to be today one of the most respected and established voices within a possible queer canon. His work differs wildly from Roberto Piva’s. Where Piva is all vision and pagan ecstasy, Costa is a cool observer of his own body and the society in which it is constantly in danger.

Somehow between the two and yet unlike both, Ismar Tirelli Neto’s poetry displays both the prowess of imagery of Piva and the sarcastic detachment one sees in some of Horácio Costa’s poems. Costa and Tirelli Neto have recently released a collaboration. In Tirelli Neto’s work I recognize by instinct a common trait in the post-war poetry by homosexuals. Due to safety in numbers in the big cities, such poetry very often manifests itself as urban poetry, and maybe due to a suspicion towards everything deemed “natural” in the West, queer poetry, especially by males, often seems to replace nature for culture in its textuality. Therefore, there seems to be a constant celebration of cultural phenomena as opposed to natural phenomena in queer poetry. The cinema, not the landscape. The human singer, not the bird. In Frank O’Hara’s words: “I can’t even enjoy a blade of grass unless I know there’s a subway handy, or a record store or some other sign that people do not totally regret life. It’s more important to confirm the least sincere. The clouds get enough attention as it is…” This apparent opposition seems to be less clear in lesbian poetry, it seems to me, and one can think of recent lesbian poets who seemed very attuned to nature such as Adrienne Rich and Mary Oliver.

5.

The current political situation in Brazil, since the election of Jair Bolsonaro, has disturbed and brought unsafety to queer authors in the country, but also energized the scene. Never before so many queers produced poetry in such a visible manner. Queer women such as Angélica Freitas, Tatiana Pequeno, Nívea Sabino, and Tatiana Nascimento. Among male queers, besides those discussed here, we should mention novelists and poets Silviano Santiago, João Silvério Trevisan, Bernardo Carvalho, Renato Negrão, Rafael Mantovani and Otávio Campos. Under the sign of Madame Satan [Madame Satã], as was known one of the gay icons of Brazil from the 1930s.