(Third Part of Three)

By Ricardo Domeneck

By 1989, when Brazilians voted for the first time after the 1964 coup d´état, the most influential among the first modernist poets, Carlos Drummond de Andrade (1902 – 1987), and two of the poets who had tried to heal the wounds left by the dualistic debates of the post-war era, Ana Cristina Cesar (1952 – 1983) and Paulo Leminski (1944 – 1989), were dead. It was the moment of a fake transition between the authoritarian military regime and an authoritarian economic regime, the 1990s, time of the relentless propaganda discourse of a triumphant capitalism. Ideas from the 1950s were still dominant and very little had been to done to re-read the post-war poetry and find new models. Poets like Hilda Hilst (1930 – 2004) and Roberto Piva (1937 – 2010), who would later become extremely important for my generation, could only be found in second-hand bookshops and were hardly discussed in the press.

This mournful moon, this unease

Inner turbulence, lagoon,

Inside the solitude, a dying body,

All this I owe to you. Such immense

Plans and future, ships,

Walls of ivory, words full

Always consented to. It would be December.

A jade horse beneath the waters

A double transparency, a line in mid-air

All these things at your fingertips

All undone through the portal of time

Silent and blue. Mornings of glass,

Wind, a hollow soul, a sun I can not see

This, too, I owe to you.

Hilda Hilst (translated by Beatriz Bastos)

There were important initiatives, such as the “Coleção Claro Enigma”, run by Augusto Massi, who began to reissue the works of poets from the 1950s and 1960s such as Maria Ângela Alvim (1926 – 1959) and Orides Fontela (1940 – 1998), and we searched for these editions like prizes.

In the 90s, we still had one major modernist model in the work of João Cabral de Melo Neto (1920 – 1999), who had taught us the lesson of “not perfuming your flower, not poeticizing your poem”. To us, it was more than a lesson in poetics, but also in ethics.

Despite the immense loss of poets that took place in the past decade (Haroldo de Campos, Hilda Hilst, Waly Salomão, Roberto Piva and Décio Pignatari are among the poets who died in the past 10 years), poetry remains one of the most active and strongest artforms in Brazil today. The most widely read and popular poet in the country is Manoel de Barros (b. 1916), a man who at 95 is still quite active and has recently released his Collected Poems. In what could easily be mistaken as simply nature poetry, Barros performs strange exercises in perception phenomenology.

from An Education on Invention

To enter the state of being a tree it’s necessary

to begin with a gecko’s amphibian torpor

at three in the afternoon in the month of August.

In two years inertia and scrub grass will begin

to expand our mouths. We will suffer

a little lyrical decomposition

until the scrub grass emerges in our speech.

For now, I have designed the smell of the trees.(translated by Idra Novey, in Birds for a Demolition. Carnegie Mellon University Press, 2010)

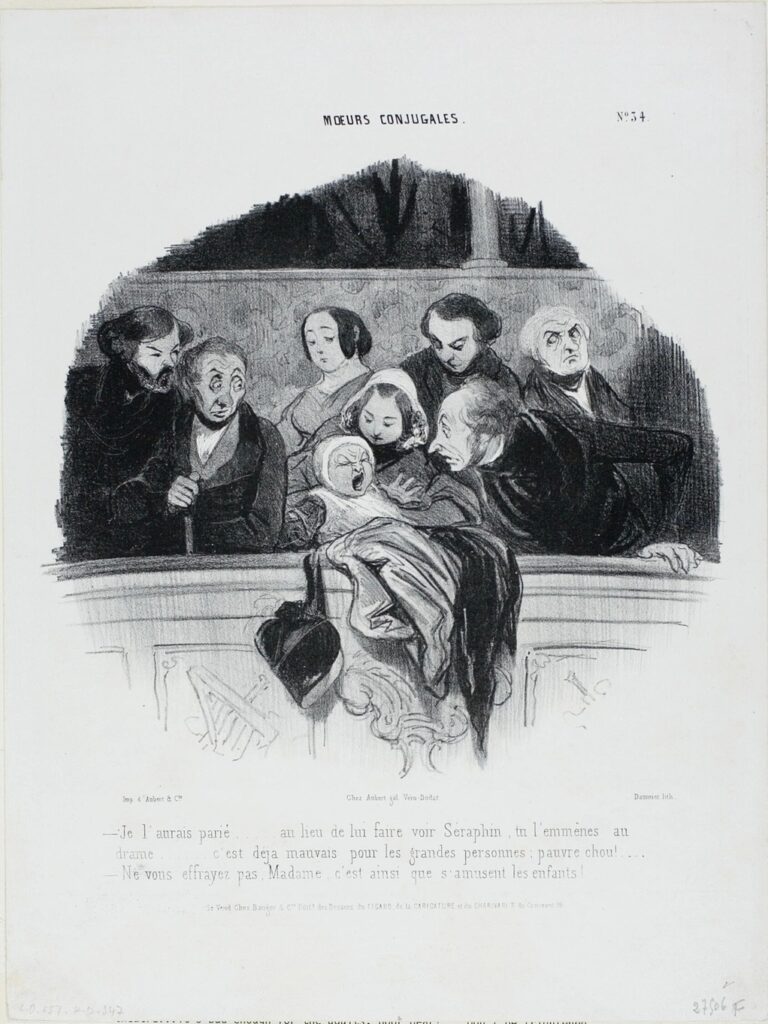

Augusto de Campos (b. 1931), the last of the three great Noigandres poets, is still a driving force in Brazilian poetics through his work as a poet, critic and translator. He continues to play a role to us similar to that of João Cabral de Melo Neto: lessons in measure. Also, his incessant curiosity and experimentation with every possible support for poetry.

Augusto de Campos, “cidade/city/cité” (performance)From the poets who started publishing in the 1980s, Horácio Costa is today one of the most active writers and professors in the country.

Portrait of Don Luís Gôngora

vampire face, life-battered nose,

stiffness your immoderate pride,

the corners of your smile drawn down without irony,

I do not see your hands, they might be writing,

they might be manipulating syntax’s abacus,

I see you absorbed in seeking dormant treasures,

larvae shimmer on the white page,

and your sphinx eyes, now fixed, penetrate me

they imitate your fan-like ears, your full cloak,

a mass of velvet or wool, Director always

of a baroque hospital before the Grand Renfermement,

for whom do you pose? You sing of the Esgueva

of your contemporaries’ thought, the radical sigh

of Nature in deep heat, lacteal language, azure field,

and you value me, Acis without, Polyphemus within,

this is the world Don Luis, you are sitting for me,

distinguished pre Kafkian cockroach goes from ante

to anteroom, patiently expounds his emphatic elastic decorum,

this much you must put up with, Jekyll without,

so small within, because you are child and beyond

the canvas’ frame you speak s blacks do—it is at night

that banality becomes a pearl, and your baldness fills the sky,

the void yields, and a lullaby escapes your word.(from Satori, 1989. Translated by Martha Black Jordan)

One extremely discrete master in Brazilian poetry today is Leonardo Fróes, born in Rio de Janeiro in 1941. His first book dates back to 1968, and several others have been issued though he has yet to become a household name, something he should definitely be. His understatement camouflages a vivid intelligence. Better known as a translator, he has given a voice in Portuguese to writers such as William Faulkner, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Malcolm Lowry, D. H. Lawrence, Jonathan Swift, George Eliot, Virginia Woolf, Rabindranath Tagore, André Maurois, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Flannery O’Connor e Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio. Having received little attention in his own country, it is unfortunately understandable that his poems have not been translated.

From the poets who became active in the 1990s, I have already spoken of Ricardo Aleixo and Marcos Siscar in the previous parts of this article. I would like to mention still Carlito Azevedo, Josely Vianna Baptista and Jussara Salazar. One of the most influential poets of the decade is certainly Carlito Azevedo, as a poet, editor and translator. Between 1997 and 2010, he issued 20 numbers of his magazine Inimigo Rumor, which played an important role in adding works to the repertoire of references that the Noigandres Group had introduced in the country. This he did, with the collaboration of several other poets and translators, by bringing to the language the work of many international poets, especially contemporary French authors like Natalie Quintane, Jacques Roubaud and Michel Deguy. Most young Brazilian poets also had their first published poems in the pages of Inimigo Rumor. As a poet, after remaining silent for 13 years, Carlito Azevedo published in 2010 his Monodrama, one of the important books of the new century and a game changer in his work, one of those books that sheds a new light and perspective over the previous work of its author.

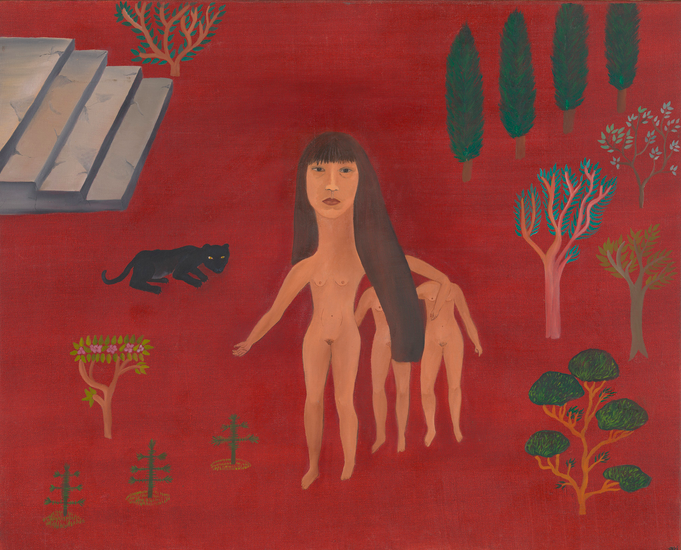

Josely Vianna Baptista has published a few books and translations of Latin American authors such as José Lezama Lima and Néstor Perlongher, along with an important work of translation of the Amerindian poetics. Her last book brings translations of three sacred songs from the Guarani Kaiowá people, along with her own poems.

Three poems by Josely Vianna Baptista

reductio

tatterdemalion habit

become hindrance,

on his way he lost

staff, cross,

his velvet cordsunseen in the forest

hunger stripped his flesh

to the spirit:

living on roots,

ripe tubercles,

faded scraps of hide,

openly he anointed himself —

a cistern hidden

in bromelia

then he saw again in dream

his childhood cradle,

his mother’s lap, the forbidden embrace

and his vain memory

became flood§

Antônio de Gouveia,*

cleric in Pernambuco

(circa 1570)gold’s priest, necromancer

well versed in magic and mine,

came to Brasil in banishment,

celebrated strange masses,

murdered imprisoned natives,

stole young women from their lovesin attempted defense

of his far-flung exploits

drafted with depraved fist

a testimonial to customs absurd

on this other side of the world

plunged his nib into a pool of anatto

(that they might suppose i dight

in blood this bitter tract),

mixing the ruddy juices

with resin from a fine cedar

(let no scribe lack sealing-

wax for sour vomit)

made tea from the fennel

he carried in a purse

and fiercely discoursed

against witch doctors’ works

(o bird of ill omen,

take this thy canting flight

and any elsewhere alight)

infused with thought,

he crept into brush,

and waking in grass,

tossed his habit in the bush

after shooing a scarab

with his leather sandals

and cleaning his shit

from his shoes with a cob

(good as any for manuring)

— ora-pro-nóbis* thorns,

noble gold of the converted! —,

without pardon for perjury,

did sign the sullied paper:From a Pernambucan hamlet

In this controverted October month,

I remain yr hmbl & obt child in Christ,

Father Antônio Gouveia.

§

air

thus how can i desire

gods in this desert so im

mense (leadgray

clouds us and venus:

cloud of clouds) , fix

gaffs in this yescraft, un

erring (leadgray

clouds this ash: ob

lique lines), if in these un

endings i mull this very begin

ning with so measured

an end (whets zinnias,

zooms up into wist

eria: steelblue gray

anulls the day), and if the world goes

on round and im

perfect at this moment

when everything is mute? (liquid words)All Josely Vianna Baptista poems translated from Baroque Patch by Chris Daniels.

Jussara Salazar was born in the Northeast of Brazil, a craddle of much of Brazilian modern poetry, and a region still with a very strong oral tradition. Songs which have long disappeared in the Iberian Pensinsula live on in the Northeast. In her last book,Carpideiras (2011), Salazar draws from an old Iberian tradition, of the carpideriras, women who are hired to mourn the dead with prayers and songs. Carpir is an old verb for “cry, lament”.

Tirana, der geheiligten, verherrlichten, heiligen Prinzessin Johanna an ihrem Totenbett gesungen.

Jussara Salazar

Sie sprach zum Herzen des Minnesängers

sing nicht/ zu den Raben

sprach sie zum tiefen Meer

die Nebel ruhen/ im Zorn

sie sprach sing nicht/ sag nur

dem Schweigen/ es soll

die Blume in die Erde bringen/

und sie zerreißt den Schatten/ dessen Hand sie

schlank wie eine hohe Nelke

umklammerte/ sprach zu der Zeit

schreck/ die Sonne nicht auf mit deinem Schmerz

Deutsche Fassung von Christian Lehnert, entstanden im Versschmuggel, Poesiefestival Berlin 2012.§

In the new century, the lines of research have become myriad, and Brazilian poets, though with a strong sense of community, seem to have become allergic to the notion of “group” or “movement”. It´s an exciting moment, with poets as diverse as Angélica Freitas, Juliana Krapp, Érica Zíngano, Fabiana Faleiros, Pádua Fernandes, Fabiano Calixto, Dirceu Villa, Marcus Fabiano Gonçalves or Érico Nogueira.

TAKKA TAKKA

Fabiano Calixto

zwischen bögen, wägen, verträgen zerrinnt das leben,

zäh, der toxische stoff hoffnung,

schon ohne geschichte, ohne die feuchtigkeit der finger

die davon kosten an den umrissen des wörterbuchs

das licht, aus der hölle erlöst, splittert

über dem tagtäglichen mut, fällt,

fällt in sich zusammen. das licht ist aderlass. schreit

dennoch (anderes licht) träume und sammlung

von hochzeiten, bei denen das glück

noch vor den nachrichten endet. deutlich, nach wie vor,

die paukenschläge, blei-ameisen

nagen an eingeweiden, morast im magen.

die kalte zärtlichkeit, mit der die dämmerung

den morgen weckt – ohne kanonen, sich entfernt

mit ihren schweren schritten, ihren

tand verwahrt im vergessen der sterne.

in den überresten der stadt (der nacht)

ein schmales, junges gesicht, unter

vom schlaf bewölkten blicken,

benday punktiert, schon fort,

läuft aus.

(übertragen von Odile Kennel. Takka Takka ist der Titel eines Gemäldes von Roy Lichtenstein)§

Keine der obigen Antworten

Dirceu Villa

Es gibt Katzen und Wollknäuel.

Die Abstraktion steckt im Zwischenraum, der zwei wahrnehmbare Dinge verbindet und ihnen auf

diese Art eine Bedeutung zuweist, will sagen, eine Bedeutung, die beide Dinge beinhaltet. Darüber

hinaus ist Abstraktion unnötig (philosophisch), brutal (politisch) oder unbedeutend (poetisch).Eliot schrieb: „das objektive Korrelat”. Goldener Schnitt der Poesie.

Es ist unmöglich, in einem Land des Mangels wie Beiwerk zu wirken.

Spektakel: das Versprechen, alles was hohl ist, oberflächlich zu erneuern, bis jemand es

bemerkt

oder zweifelt, und dann folgt erneut Erneuerung vom Nichts aus.

Die kindische Illusion, wir befänden uns auf dem Gipfel der Zivilisation.

Die Arbeit des Dichters besteht unter anderem darin, die Dinge von ihrem Ort zu entfernen, sieabzusondern, oder bis dato unsichtbare, wesentliche Beziehungen zu knüpfen.

Wir sind durchdrungen von einer Kultur des Todes und der Gnade, d.h. römische

Arena, Taschenmetapher für nach Lumpen hungernde Massen.

Ein Mensch ohne Meister bildet sich selbst und grüßt die, die berühmt sind.

Fortschritt der Intelligenz: vom Schöpferischen zum Instrumentellen.

Die Poesie ist nicht tot, die Dichter haben nur geschlafen (Jean Cocteau).Und die Moral: Wenn du nicht lächelst, stimmt mit deinen Lippen etwas nicht.

(translated by Odile Kennel, in Neue Rundschau 124)

§

The Cleaver

Dirceu Villa

Bones. Sometimes, yellow lard on the bones;

and sometimes, red blood in the nails.

There are pigs, or heads of pigs,

they hang the heads on a hook,

or the pigs’ stupid face of death

in the dim glass of a slaughterhouse.

Or the white, but a white soaked in pink,

gore in the dreaming of guts,

dreams the butcher: of handling a cleaver.

And the white apron that drenches in,

or drinks the blood springing from nerves

in a hug with the bones, where the cleaver strikes,

and how it gleams the cleaver that cuts:

that’s the virtue of steel in the fist going up,

or the threat of the empty circle that hangs it

on the slaughterhouse wall, to the naked eye,

announcement of cut. Or pricks the edge in a rock,

and the one empty eye concentrates, waiting for meat.

Stabs in the rock slashed with blood,

or cracks, from where death comes lurking

the butcher in his dream of red, stroking

the keen edge, the sneaky smile of the cleaver,

that cuts. And then the cleaver is something else:

not pigs, nor nerves, nor bones,

not even the butcher that dreams it,

but extended part of the vibrating arm

and indelible part of what it maims,

the keen edge, the sneaky smile of the cleaver, that cuts.§

Marcus Fabiano Gonçalves´s poems provide great challenges to a translator. Probing the Cratylus question, Gonçalves often operates on the border of sound and sense, its equivalence relations. His vocabulary is extremely precise, with attention to each detail, and the structure of the poems draw on sound, especially internal rhymes and alliteration, for its meanings. A sample in Portuguese, as there are no translations.

A máquina do fundo

Marcus Fabiano Gonçalves

a pesca escassa, o rio poluído, a cotação do dracma

um heraclítico engenho rege o mundo das máquinas

na margem, a draga do imponderável rio sem fundo

sem opor o puro ao sujo, aceitando o fluxo de tudo

a lama negra das imagens infiltra o oco dos crânios

no entulho da palavra gaga, a jaula do orangotango

reúne uns cacos de naufrágio, enjambra umas tábuas

vê se salva a ave da linguagem nessa arca de sucata

une o conteúdo à sua forma mais perfeita e intransitiva

e embora toda solda, cuida de mantê-la móvel e flexível

coa a lama toda dessa draga e separa bem tua saliva

retém a gota e o grão no sorriso amarelo das espigas

observa o dedo lerdo catando seu milho na datilografia

de grão em grão germina um corvo no ventre da galinha

chocando a ave faz esfinge de quem ignora o enigma

mas na verdade ela bem sabe que no fundo nada finda.§

Érico Nogueira has translated Horace, Vergil and recently published his translation of the complete Idylls of Theocritus. His two published collections of poems draw from the Latin and Iberian traditions, renewing them with his historical consciousness, though one clearly feels his nostalgia for a Golden Age. It is one of his main themes and I have called him at times an “unrepenting HughSelwyn Mauberley”.On the Tip of My Tongue (3 of a 9-section poem)

Érico Nogueira, translation by Chris Miller

1.

It’s always the same: punch your card at the exit,

‘Ufa—at last…’ and ‘No more to-bloody-day’:

‘Step on it’, you think, though your mind is still

Bubbling with Eve-tease and worse things yet;

Down the road, it gets beautiful; yo! The sunset,

The meadow is a promise but a purgatory too,

That same old uneasiness sweats over everything

Recalcitrant especially to anything with wit;

The skinnamalink voice of the rebec (not

Rebecca!) jangles up the rhythm with its

See-saw bow. Drum! A punch to the schnozzle,

Another! Doh, damn jasmine-scented night!

A wind gets up, almost home, now here’s a wood

(Was that always there?)—and it’s calling your name,

Your true, your secret name, not the one on your tag;

Up top the moon, well, illuminates—not much,

And you on the bottom stair of not much either;

A touch of frost; warm bed; yep, that’s the way it goes.

2.

Anything rather than sleep: meaning life outside the window,

the Milky Way and all those confusing constellations,

stars glimmering now here now there—if you should care to look;

it’s the stuff night does. Why? Don’t ask me, it was God

set all that up—I could tell you more by daylight,

when the head’s just doing its thing, not thinking,

and there’s more of the world; now,

what with no light, no noise, it’s a pig—and life itself

is less itself (or maybe more?)—I said: a pig,

having to get up and go for a piss, and there, yes,

bonkers at the mirror’s gleam, to have the guts to look;

clock, mirror, lost souls, discombobulating rubbish;

and I forgot, it only comes by night, like someone not sure

what they want, coming to get you, matey, merciless they are…

So look! Head up; look in the bloody mirror:

nothing so terrible, nothing so specially ugly,

nothing as bad as Monday after a long weekend;

darkness is good for you; darkness loves you, babe.

3.

Saying ‘Yo tengo miedo’ and ‘No, no puedo, gracias’

Isn’t going to save you just because it’s Spanish,

It doesn’t change a thing; and yes, it really is raining,

And you’re stuck here, with a million things to do,

Thinking: But it’ll rain on me, surely I’ll dissolve…

Go on out then, there’s nothing else to do;

On the corner, ‘A taxi, a taxi’, that’s your mantra

—till one comes: ‘Where to?’ ‘The airport’.

‘A plane for Rome, asap! ‘For Rome, it’s quite a wait:

Is Athens any good?’ ‘Now?’ ‘This very instant;

Unconditional embarcation.’ ‘Unconditional?

Would that be “international”, do you think?’

‘Hear what you like’ (Stupid cow.) (What a sucker…)

‘This way.’ Those German verses lurking in your case:

Open the book, the wine-dark pummelling the cliffs,

And that mountain, or another, with its snow-capped

Peak, and lots of grapes, and the touristic glimmer

Of the dinky little Greece those Germans just adore…§

Penelope (i-iv)

Ana Martins Marques translated by Julia Sanches. Originally published in Modern Poetry in Translation.

(i)

What day knits

night forgets.

What day traces

night erases.

By day, threads,

by night, tracks.

By day, silk,

by night, loss.

By day, cloth,

by night, fault.

(ii)

Day’s plot

in night’s yarn

or night’s plot

in day’s yarn

as I spin:

fidelity by a thread.

(iii)

By day thimbles.

At night no one.

(iv)

And she did not say

I am no longer yours

I gave my heart to quiet a long time ago

while your heart swayed in travel

as I waned

amongst the night’s drapes

you traversed unsuspected distances

the charmed bodies of women whose strange language

I could use to spin a shroud

of our common tongue.

And she did not say

in the beginning I thought of you

first as one who burns before

a dying campfire

later as one who, remembering, visits childhood shores

and then as one who recalls a long summer

and later as one who forgets.

And she also did not say

loneliness can come in many forms,

as many as there are foreign lands,

and it is always welcoming.§

Mermaid in earnest

Angélica Freitas translated by Hilary Kaplan

the cruelest part was that as beautiful

as much as her features flaunted

a genetic pedigree of bonafide aristocracy

and her hands deftly wielded

needlework and roast chickens

and her tresses attested

to tortoiseshell combs and splendid grooming

the fascination would always remain

with the mermaid’s taili won’t repeat the story

after andersen & co

we all know the rough path

first the impossible desire

for the prince (doll in formal attire)

then awareness

of powerful witchcraftin exchange she gives something up

her voice, her elastic hymen

her club med membership cardit is a difficult process

feminine bipeds are fooling themselves

attributing to high heels

the pain more properly ascribed to haughtiness

seeing as

the mermaid treads on knives when she uses her feetand who takes her seriously?

the ending would be better if

instead of the elephant that dances

in her head when she sees the prince

and the 36 fingers

that sprout when she offers her handshe regained her tail

and never shaved againOver 20 years after the end of the Military Dictatorship which silenced so many artists, we have now a new generation, coming of age in the mid 2000s, who unlike some of their predecessors of the past 30 years, strike me as far more conscious of the historicity and political/contextual implications of their practices. They have ceased to oppose the poetic function to the referential function in language, as if one obliterated the other, and seem now to work on the border of transparency and non-transparency of the sign. Minding materiality and concreteness, they understand the opaqueness of the word in poetry, without simply practicing the visual theatralization of the sign, as we often saw both in the Concrete poets and their heirs. They seem to accept the challenge in Susan Howe´s question, in her My Emily Dickinson:

“Who polices questions of grammar, parts of speech, connection, and connotation? Whose order is shut inside the structure of a sentence?”

I wish I could have shown more poems in this articles. Unfortunately, so few of these poets have been translated abroad, as is the case of some of those I respect the most, Marcus Fabiano Gonçalves and Juliana Krapp among them. Some of the most fascinating creatures to emerge in the past couple of years, like Reuben da Cunha Rocha and William Zeytounlian, have barely been published in bookform in Brazil. Maybe this effort can change that scenery, and this article can became an ongoing process. Though I have few hopes of that, as I dont expect this planet to survive much longer.

Ricardo Domeneck

Berlin, April 2014This article is part of a collaboration between Babelsprech, Hilda Magazine, Full Stop and Samplekanon.Read the first part of this article. Read the second part here.