On the Making of a Crowded Photograph, Including Some People in the Background (Part 2 of 2)

Postmodernism

How to talk about postmodernism when the term ‘postmodern’ can be applied as easily to a Pynchon novel as to a microbrewed beer? As likely as anywhere else, the term ‘postmodernism’, when applied to Dutch poetry, is prone to cause confusion and contestation. It would of course be possible to collect a list of stylistic characteristics commonly attributed to postmodernism, but it might be better to account for local specificities here first. First of all, postmodernism means something different in Flanders than it does in The Netherlands. Whereas it in The Netherlands it is mostly associated with a culture of ‘anything goes’, in Flanders it was more serious and theory-inflected, perhaps due to its proximity to the French-speaking world. Flemish poets such as Dirk van Bastelaere (1960), Stefan Hertmans (1956), Erik Spinoy (1960) and to a lesser extent Peter Verhelst (1962) digested the work of philosophers like Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, François Lyotard and others, with the aim of constructing an anti-essentialist discourse about poetry. In a classically avant-gardist way, they attacked the prevailing conservative and (neo-)romantic attitudes towards poetry, found in for example the work of Leonard Nolens (1947) and Herman De Coninck (1944-1947), two influential Flemish poets of the post-war generation.

Around the same time – end of the eighties, beginning of the nineties – the Dutch poetry world was rocked by the Maximalen (Maximal Poets). They formed a group, published an anthology, performed together, but did not self-identify as postmodern, even if their poetry was the product of a general postmodern, cultural atmosphere. They favored impure, urbane and worldly poetry above the clean and ‘cold’ aesthetic of the pervasive (late) modernism of that period, in which the poem as autonomous artifact was dissociated from the world, and they rejected hallmark poets of the modernist era like Gerrit Kouwenaar, Hans Faverey and their ‘acolytes’. The poetry of the Maximalen was however not very theoretically sophisticated: rather, it was a highly mediatized event in poetry, not for its linguistic innovation per se but for its appearance, its role in the emerging commercialization of poetry. It should not be surprising that many poets associated with the Maximalen, such as Pieter Boskma (1956), René Huigen (1962) and Joost Zwagerman (1963) went on to develop very different careers, including a variety of styles and attitudes towards poetry, from neoromantic (Boskma) to an almost paradoxical return to modernism and dense intertextuality (Huigen). A combined trait is an appetite for aestheticized linguistic play, whereas in Flanders there were discussions around the ethical, ideological, critical and not just about the aesthetic aspects of postmodernism. Ideological discussion, in turn, were (and still are) denounced as old-fashioned moralism by many people in the poetry world in the Netherlands.

This aesthetic of playfulness was, and still is, a dominant way of understanding this type of poetry, as can be seen in the reception of innovative poets like Tonnus Oosterhoff (1953), Astrid Lampe (1955), Arjen Duinker (1956), Nachoem Wijnberg (1961) and younger poets like Mustafa Stitou (1974). Unlike the Flemish postmodernists, they didn’t manifest themselves as a group and many even didn’t identify with the label of postmodernism (some were only retroactively fitted into this category in academic criticism, such as Arjen Duinker). While considered willfully obscure, ‘hermetic’ poets by some critics, their work is rather formally open, eclectic, and in a way, democratic: the lyric I is no longer the central creative instance, other texts and voices enter the poem. Perhaps even more characteristically, many of the aforementioned poets don’t dismiss forms like anecdote or the lyric poem; rather, they use them with a postmodern collage consciousness and sense of textual artifice. These forms may be constructs, but they can still be used to chart how language moves through the world, and the place of the subject within it. Consider for example these lines by Tonnus Oosterhoff’s, perhaps his most famous:

“You’re so honest, so unassuming.”

“I like it that way!”

It is a pleasure

to be Tonnus Oosterhoff.

“Wouldn’t mind it myself.”

Sure, but you can’t!

You can’t.

Translation by Samuel Vriezen.

Unless noted otherwise, translations are our own.

Knowing that there is no stable self, this poem nevertheless performs it. This ironic performance, in which the reader can follow the process through which writing happens, is typical for Oosterhoff’s work and for many other poets of his generation: the influence of this poetics is wide and includes Alfred Schaffer (1973), one of the earliest readers of John Ashbery’s work in The Netherlands, but also Martijn den Ouden (1983), mentioned earlier, and others. Tonnus Oosterhoff’s experiments continue to find new visual forms through his recent forays into digital poetry, for which he was a Dutch pioneer.

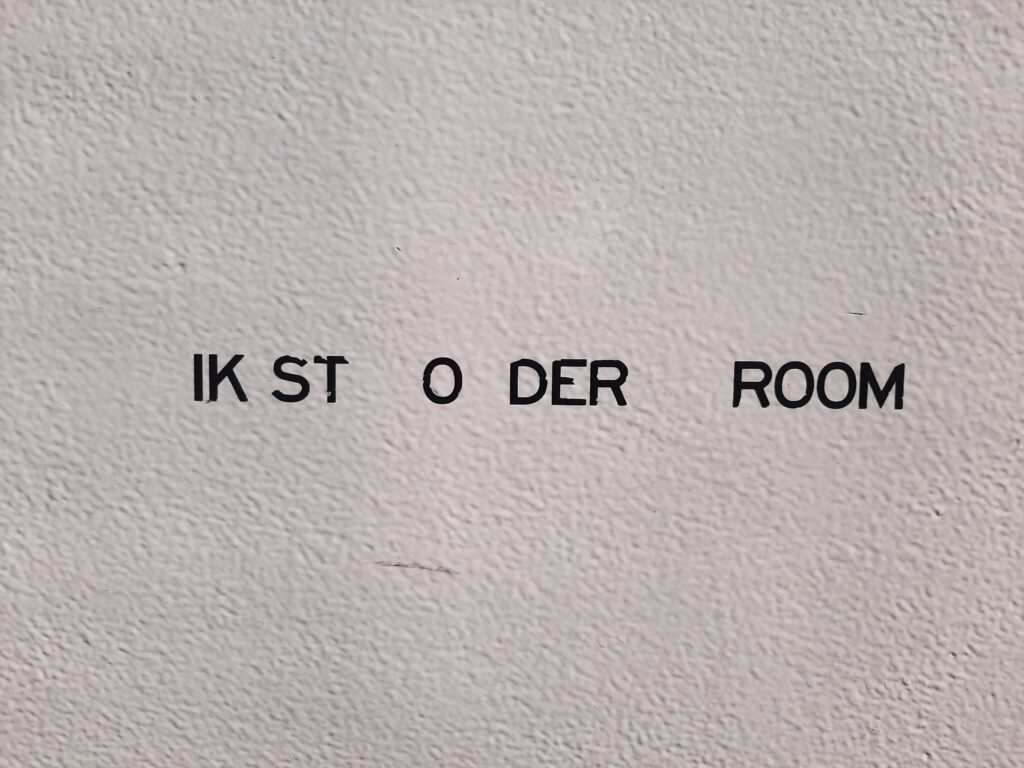

One young Flemish poet working in a postmodern vein (or re-working it) is Sandrine Verstraete (1986). Verstraete works across different media: installation, theater but also regular print books. Her debut collection r mp (r mp – suggesting a truncated spelling of the Dutch word ‘romp’, meaning ‘trunk’) came out in 2013. As is the case in many postmodern texts, language has a viral quality in her work, it mutates and shape-shifts continually. Her work is both performative, lyric and conceptual, and exemplifies a struggle for immediacy, intimacy and live contact. The fragment below is from her installation ‘Hollow’, and provides a fine example of how Verstraete works her way through language in order to reach a smoothness that feels real and intimate, like skin:

Chaos before and chaos after

and here the silence

safely

locked

still

was a spiral

it sucked

my insides towards itself

hands have picked me up

and put me in this cradle

a face almost familiar

a breath sounding

and everything I see is skin

rest my head against a wall

like it was something human

and everything I see is skin

Translation by Sandrine Verstraete.

One of Verstraete’s examples in terms of the use she makes of textuality is the aforementioned poet, novelist and dramatist Peter Verhelst, who himself called Verstraete’s work ‘visceral’. Verhelst is hailed as one of the foremost postmodern writers in Dutch. His breakthrough novel Tongkat (Tongue Cat, 1999) is a highly allusive, fairytale-like ‘story brothel’ (the subtitle of the book) with an innovative, mosaic-like structure. He is also highly prolific poet. To cite one poem from his vast body of work:

Vase

Can you blame a vase for its fragility

or a hand for breaking the vase?

Maybe it is meant for this;

for the vase to sing down upon the hand,

until the hand can no longer resist,

even though the hand knows it will hit

and the shards already singing in the vase

before they were made.

Why would the hand long for a vase,

which like a neck, extends towards the hand

that is about to hit it? And why does the vase

want to sing its shards to the surface

until the hand is unable to resist?

Maybe the vase is dreaming of the hand,

turning it into a rose, and the hand seeks out the vase

to finally find the shard

with which he can beat roses from the wrist.

Translation by Astrid Alben, courtesy of Poetry International.

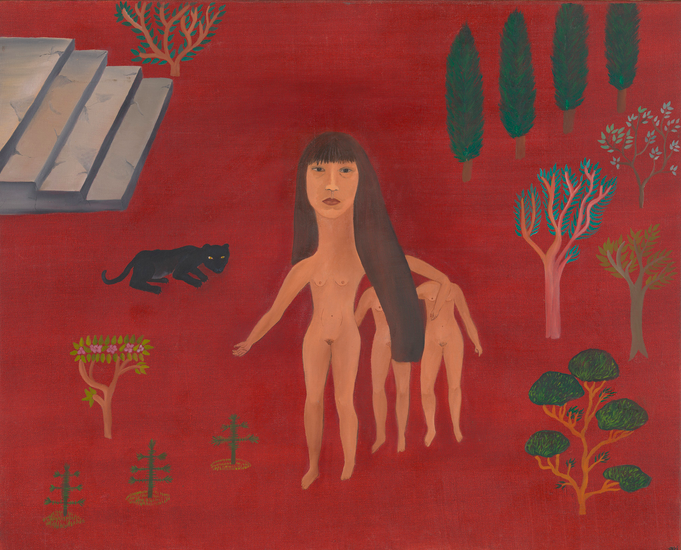

While both Verhelst and Verstraete could be seen as postmodern poets, one could also see them move beyond it. Some critics have located a turn towards ‘new sincerity’ and sentimentality in their work – perhaps as a response to its lack of authenticity, and the desire to infuse the ‘real flesh’ of bodies into the ascetic and disembodied reality of postmodernity, with all its signs and simulacra.

*

One of the most interesting and polemical voices in recent Dutch literature was the Dutch poet, blogger and literary scholar Jeroen Mettes (1978-2006). Like the Flemish postmodernists, Mettes digested poststructuralist thought (which was still rather absent in Dutch poetic and public discourse back then), but he was also very knowledgeable about American experimental poetry of the last century, including the language poets, the New York School, the San Francisco Renaissance and the Black Mountain Poets. Mettes entered Dutch poetry from almost nowhere in 2005 when he started his blog Poëzienotities (Poetry Notes). Poet Samuel Vriezen, one of his earliest on-line correspondents, wrote about what made Mettes so remarkable in the Dutch context: ‘Mettes read poetry for political reasons, to see whether poetry could offer him a way to deal with a political world he detested. The right-wing horrors of the Bush years, the Iraq war, and the turn of Dutch public opinion towards ever more conservative, narrow-minded, and xenophobic views alongside a complete failure of the political left to present any credible alternative, were weighing heavily on the times in which Mettes reported on his reading.’

Mettes rose to attention due to the so called Dichtersalfabet (Poet’s Alphabet), in which he alphabetically reviewed the poetry books he bought off the shelves at the book store Verwijs in The Hague, where he lived. The project was as random and theoretically astute as it was polemical and illuminating. In these blogs as well as in his essays, Mettes attacked two dominant strains in canonical Dutch poetry: a poetics of the ‘postmodern sublime’, by which he meant the awe-inspired realization that any full representation of reality was impossible, and a poetics of everyday wonder – the confluence of which he saw as a display of the logic of the commodity, resulting in a quietist attitude towards reality as something unchangeable. The affirmative quality of the poetry of K. Michel (1958) and Arjen Duinker left no room for negation or ideological conflict, according to Mettes. He also opposed romantic attitudes in poetry, visible in the slam community, which he wrote off as kleinkunstpoëzie (‘cabaret poetry’, stage poetry that intends to entertain its audience).

Mettes’ own poetic output was heavily influenced by American language writing, especially Ron Silliman’s paratactical New Sentence, which he explicitly referred to in the Poetics Statement preceding his two hundred page long New Sentence epic N30, the code name for the antiglobalist protests in Seattle in 1999. His work could be described as taking a position somewhere midway between Ron Silliman’s ‘pseudo-autobiographical’ writing – Jeroen Mettes, like Silliman, often writes himself into the fabric of the text – and Bruce Andrews’ highly disjunctive, subjectless assemblages. Here is a fragment:

Chapter 1

A day is a space too.

And another man, who had chained himself, had his ribs crushed, and a motor has driven over somebody’s legs.

Dutch health care system spends ±145 million guilders per year on worriers.

A spiderweb vibrates as I pass by.

Randstad renovating.

She slaps her bag against her ass: “Hurry up!”

OPINION IS TRUE FRIENDSHIP

Your skin.

It doesn’t express anything.

“But the use of the sword, that’s what I learned, and you’ll need nothing more for the moment.”

Just try to interrogate a guy like that.

Gullit in Sierra Leone.

Codes silently lying all around.

But that’s simply what belongs to “that it’s just allowed”: that sigh of “world” (a word expressing that the trees are now standing along the water like black men with white bags in their hair); that’s nothing else right?

And you see how everything has to move, and first of all what cannot do so.

Without Elysium and without savings, barbarians lashing out, horny for an enemy, staring across the water, staring into the air—staring to get out of it.

“You’ve never showed me more than the mall,” she said.

All those “dreams” in the end—and now?

It was lying on the stairway, so I picked it up and took it upstairs.

It is difficult to outline the influence of Mettes’ work, also because it only circulates widely since 2011, when his posthumous works were finally published. It should be said that here certainly has been a move towards politicization among poets over the last decade and a surge of new interest in American experimental writing over the last few years. But this is not unequivocally attributable to Mettes’ blog, although his works are definitely referred to. Samuel Vriezen (1973), a poet and composer, has introduced many American poets in Dutch translation, through literary magazines like Parmentier, Yang and later nY, and new ways of thinking the relationship between politics and aesthetics are central to his work. His latest chapbook 1512 consists of 1512 words and 21 sentences of 6 words that are constantly rearranged, often to highly critical effect.

Arnoud van Adrichem (1978), a Dutch poet who used to be the editor-in-chief the journal Parmentier was also highly influenced by American writers, especially Ron Silliman and other poets who write in a paratactical styles. By using imperative sentences, like ‘Say it in your own words’ or ‘Say: tropical forest. Does your bathroom look different now?’, Van Adrichem evokes an authoritarian, empty voice, signaling the invisibility of power and investigating the interplay between power and language. And the young Dutch poet Çağlar Köseoğlu (1983) uses parataxis to explore the socio-political reality of present-day Turkey and its violent histories, especially with respect to the Kurdish people.

In Flanders, Xavier Roelens (1976) has developed a documentary poetics that is informed by many American writers, among them Juliana Spahr. In his most recent book Stormen Olielekken Motetten (Storms Oil Leaks Motets, 2012), he uses lists, songs (often multilingual) and fragments of speech to evoke ecological catastrophe and his personal complicity with it. Tom Van de Voorde, Dutch translator of Michael Palmer’s work, is another Flemish poet with an interest in the American experimental tradition. International influences can also be traced in the work of some emerging poets, for example Arno van Vlierberghe (1990) and Mathijs Tratsaert (1992), who started the poetic collective Omfloerst (Shrouded), based in Ghent. They critically appropriate the Flemish canon, from the decadent and romantic poetry Leonard Nolens to the politically inclined postmodern Dirk van Bastelaere. Tratsaert’s ‘Nieuwe Vlaamse gedichten’ (New Flemish Poems) seem to be influenced by Mettes’ collage-like technique, but also take cues from new forms of confessional (or quasi-confessional) idiom:

My name is Mathijs Tratsaert. I am humorless and write poetry. My friends write poetry too. I make copies of myself and put them in bed. I am suffering from amphibrachic glossolalia Eloi Eloi anonymous.

The Internet is a leftist. The 21st century woman is a Pygmalion machine and my ex-girlfriend is a Zen Buddhist. I make copies of myself and put them in a poem because I have absolutely nothing to hide. Ha ha ha I roar with laughter. It was only yesterday that I bought leather shoes.

*

Another new international development that arose in Dutch poetry the past ten years is flarf poetry. Like the renewed interest in language writing and writers associated with the New York School of Poetry, Flarf also contributed greatly to expanding the range of poetic forms and materials available in The Netherlands. Introduced by Ton van ‘t Hof (1959) – more on him later – the flarf aesthetic was picked up by a various poets, among them Mark van der Schaaf (1966), Nanne Nauta (1959), Sven Staelens (1979) and Jeroen van Rooij (1978). The latter sampled fragments from a well-known website for amateur poetry, dichttalent.nl; Nanne Nauta, interested in Oulipo writers, fed the articles from the Universal Declaration for the Rights of Men to Google and rewrote them using the results. Techniques like these produce the polyphony typical of flarf poetry, a collage of disembodied voices from the internet’s underbelly; in Midlife motivator (2012), Mark van der Schaaf employs a ‘low style’, partly pornographic and partly inspired by kitschy stock motives from bouquet romance to deconstruct masculinity.

Ton van ‘t Hof (1959), in the first ever Dutch flarf collection Je komt er wel bovenop (You’ll make it through, 2007), wrote the poem ‘Nederland is groot’ (The Netherlands are great) using the recurring title phrase as his source material. Basically, the sequence consists of a collection of lines bragging about the greatness of The Netherlands (or maybe, the virtues of its ‘smallness’), highlighting the absurdities and ambiguities of nationalist discourse. It is an attempt to think The Netherlands as a political entity, and was written at a time when right-wing discourse was increasingly gaining influence. Aan een ster / she argued (To a star / she argued, 2009), his third volume, written when stationed in Afghanistan – Van ‘t Hof has worked as a colonel in the Dutch army – uses both flarf and conceptual techniques to register the disorienting effects of war on the subject, and the author’s complicity with it. Generally however, the poetic output of the Dutch flarf collective seems to be less political and brutal in its overall tone than the writings of their American counterparts. In 2011, the word flarf entered the Dutch dictionary, and so we could conclude that flarf has started to run its course.

*

Another tendency in young Dutch poetry worth noticing is a poetry of direct utterance and thinking aloud. Lieke Marsman (1990) is a strong representative of this. Her first volume of poetry Wat ik mijzelf graag voorhoud (What I like to impress on myself, 2010) was awarded three prizes for best collection of the year. Her work is sometimes called confessional, and Wat ik mijzelf graag voorhoud is classical in tone. Simultaneously, her work is highly reflective of the moment of its utterance, in a manner that reminisces American poetry in the first person. A lot of poems are diary-like, messy, and while they strive for presentness, they can often elude the reader – as is clear from this poem:

IF ONE COULD GO DOWN IN HISTORY AND TELL IT IT MUST STAND BY ME

When I was fifteen, I drank alcohol for the first time at New Year’s Eve, after which the world started spinning. The world was already spinning, but in the form of tennis balls, tops, the wheel of fortune, my father’s eyes when he made a sarcastic remark, perhaps, and this was more real. I thought I’d finally be able to phone without shivering, but it didn’t give me wings, or knock me out for weeks.

When I was eleven, I stuck pictures of my favorite pop stars on the cover of my Winnie-the-Pooh diary in the hope that it would make the content more serious, more worldly. Text turned out not to be so easily fooled and in an attempt to save my past, I next tried to set fire to the book. Because I was frightened of matches, I took it to the paper recycling bin a few days later.

When I was sixty-eight, I wrote my first poems about love, in which I didn’t have to compare it to animals or plants. Love consisted of two contented people, lay down tired but satiated in my belly, the navel of which still like a lizard on a sunny stone.

When I was five, I dreamt it was snowing, though no one had told me there was a chance it might actually snow. It could have rained all night. I woke up and the world was as white as my five-year-old skin. That was the first time I thought I could change the world.

Translation by Paul Vincent, courtesey of deBuren.

Her second volume De eerste letter (The first letter, 2014) is less classical in tone than her debut, and more characterized by self-doubt and angst. The importance of the first person singular is even more clear here: this second volume contains a poem that rewrites (and subverts) Kenneth Koch’s rewriting of Williams Carlos Williams’ famous poem ‘This is just to say’.

A Flemish poet that has emerged recently is Delphine Lecompte (1978). She published her first volume, De dieren in mij (The Animals Within Me, 2010) with the Contrabas, a small poetry press in The Netherlands. To critical acclaim: it won the Buddingh’ Prize for the best debut collection of poetry of that year. She writes obsessive, compulsive and disordered lines, with a hint of the grotesque and the surreal, sometimes reminding of the work of Paul Snoek (1933-1981). Here is a typical poem:

I get up to make yesterday into the day before yesterday

I get up to think about yesterday

Yesterday I wrote a bad poem

But I thought it was great

Yesterday I washed an aphasic woman

And stole a culinary magazine

From the waiting room at my mother’s gynaecologist’s.

The aphasic woman was called Martha

She used to be a truffle grater in a factory

I haven’t looked at the culinary magazine yet

My mother’s still got a uterus

But she doesn’t use it.

After thinking about yesterday

I contemplate the day before yesterday

The day before yesterday I didn’t wash anybody

Especially myself

I didn’t steal any magazines

My father wrote to me on a postcard of a grazing zebra

That he was proud of his nursing daughter who had given birth

To a son without a harelip

The trunk of the plane tree was wet

With an Irish tourist’s urine.

The Irish tourist wanted to murder me yesterday

I don’t want to think about that too long

After all, it’s today that matters

Now

Now I’ve re-read my poem

Again it’s not great.

Translated by Rosalind Buck, courtesy of Poetry International.

Anne Broeksma (1987), whose first book of poetry Regen kosmos kamerplant (Rain Cosmos Living Room Plant) came out in 2014, shares a certain directness with these poets. Her work reports about everyday awkward situations, using imagery that is dark and comical. Something in her work reminds us of Tonnus Oosterhoff’s often grotesque humor and subject matter. In a self-referential bent, her poem ‘Poking in the eyes with a small stick’ turns the traditional search for ‘important subjects’ into the poem itself:

Poking in the eyes with a small stick

Every time I think I have found important subjects

I am compelled to pinch myself. There’s only one important subject

and it is:

you as a hook-lipped rhinoceros on a savannah walking away and away

to hide behind a bush, though you are mine. I just think

I can have you as my own and mangle your eyes with a small stick.

It’s for fun and it has a name. Then I say:

‘What is it what is it’ and then I give the answer myself:

‘Poking in the eyes with a small stick.’

It’s an autistic ritual but it makes me happy.

It is my most important subject in the world.

*

While not a poet of direct expression per se, Dennis Gaens (1982) nonetheless has something in common with the poets above: the use of narrative. He reports in a direct way about life, community and social situations in his work, but often his poems fail to deliver a complete story: they are snapshots of something larger that seems to be lacking. The title of his first book Ik en mijn mensen (Me and my people, 2010) sums this up nicely, as does this poem from the same book:

Sneakers

There are times when we feel like chaining ourselves to this very spot until we have resumed thinking in our mother tongue, although this is rare. We usually wake up facing the street, our clothes folded along the edge of the bed. The door left open from last night.

Our sneakers were made for short distances and yet we tread the city streets, make little detours so we can kick tin cans. Especially when it comes to half litres; our eyes full of intent for a second.

There are days on which we see a father figure in everyone and then again only in him and despite everything. There are enough stories here and you can buy something to eat on every corner. Our feet bounce, full of confidence.

We are a kind of pact, I and this plural, and our strolling is all we have.

Translated by Jop Luberti.

There is a social drive for writing in Gaens’ poetry. He collaborates with musicians and makes zines, which also speaks to the desire for poetry to be involved, materially, in some sort of community.

This he has in common with Maud Vanhauwaert (1987), a young poet from Flanders with a background in theater and writing for performance. Apart from writing poetry, she does all kinds of ‘public’, in situ work – for example, quoting lines of poetry to strangers in the streets, or confronting them with poetry in some other direct way. This clip, titled ‘Poetry & Public’, shows Maud Vanhauwaert citing the line ‘Shall we wait’ to people walking through Antwerp:

For Vanhauwaert and Gaens, poetry is something that exists off the page as well, as something bodily present, alive and active, moving through language – something that could also be said of Anne Broeksma’s and Lieke Marsman’s work, or that of the young Dutch poet Hannah van Binsbergen (1993).

*

This piece ends here. It has haunted us as we wrote it. We don’t expect that this will end by finishing it. Defining the situation you are part of is a strange and wonderful thing, but stirs up confusion, the fear of not being able to communicate what it feels like to live and write in The Netherlands today. We are in Frank’s house, in Amsterdam-Noord, in a street that suddenly reminds us of Frits van Egters – a character created by Gerard Reve in his famous novel De avonden (The Evenings, 1947) – joking around because he feels entrapped in the bourgeois life of the postwar Fifties. We want to thank all people we talked to about this piece and who, knowingly or unknowingly, contributed to it.

Maarten van der Graaff & Frank Keizer, January 2015