On the Making of a Crowded Photograph, Including Some People in the Background

Disclaimers

As articles like these often start with a series of disclaimers, a logical place to start would be explaining the linguistic and political situation in which the Dutch language and corresponding literary systems are embedded. Dutch is spoken by more or less 23 million people across the world, most of which live in the Netherlands and Belgium, and because of this, and also due to the historical importance of the Dutch language, Dutch is sometimes called “the smallest world language”.

In Belgium, Dutch is spoken in Flanders, the northern part of the country. Apart from a negligible number of idiomatic phrases and regional differences that result in everyday confusion at most, people from Flanders and the Netherlands mutually understand each other quite easily. Cultural exchange between the two countries followed, and writers are read and discussed in both cultural spheres alike, in magazines, newspapers and academia, resulting in both literatures becoming increasingly intertwined, institutionally.

But the extent of this exchange should not be overstated – Flemish authors are not regularly part of the Dutch public discourse, although hypes do cross the border, and Dutch authors, a little more known in Flanders perhaps than their Flemish counterparts in the Netherlands, do not take the center stage in the Flemish media. Discussions on poetics have local idiosyncrasies and the countries’ respective histories are markedly different. All this makes the decision to treat Flemish literature alongside, or even as a part of Dutch literature, controversial. Indeed, one of the rifts in literary history and historiography in the Low Countries is the question whether the Dutch and Flemish literary systems should be treated as one, or be considered as separate entities, with largely independent trajectories.

There are good reasons for this. Most importantly, the linguistic situation has, historically, been different. Belgium is a trilingual country, with Dutch being the majority language in Flanders, whereas French is the dominant language spoken in Wallonia, the southern part of the country, adjacent to France. The southern part of the country also has a few German communities. This has caused conflict for a long time. Specifically, Flanders had to fight for equal language rights for the Dutch speaking population. French held a cultural and political monopoly, reducing Dutch to the status of a minority language only used by the working class for much of the nineteenth and early twentieth century. While this has now been reversed, the relationship between the two communities is still problematic.

Due to this linguistic and political situation, Flemish literature (up to World War II, and even after), was part of the emancipatory (and in many respects, nationalist) Flemish Movement, as it was called, that sought, in short, cultural and political recognition of the Flemish-speaking community. Poets like Guido Gezelle, the poet-priest, and Paul van Ostaijen, a Flemish nationalist and member of the international avant-garde, were never just poets, but also fulfilled a foundational role in the emancipation of the Flemish language. Van Ostaijen remains the bedrock of almost every discussion pertaining to poetics in Flanders, even today, as was argued by a voluminous study undertaken by Geert Buelens in 2001. Dutch literature lacks such a towering figure.

To further corroborate this: one historiographer stated, back in 1990, that one can discern in fact three different literatures – Dutch literature, Flemish literature and Flemish literature insofar that it is known by Dutch publishing houses, that hold a hegemonic position compared to their Flemish counterparts. Lumping the first and the third one together would be an act of imperialism, a severe misrepresentation of the cultural situation in Flanders. More recently, in 2008, three poets published an anthology, Hotel New Flanders, that contained only Flemish poetry, asserting that there was no sound historical reason to treat Dutch and Flemish poetry as if they were part of the same system.

We could be economical and brush over these differences in this piece, or be exhaustive and go into depth on this matter, but neither is desirable. First of all, we do not write as professional scholars, who are required to adopt a systematic approach to literature, but as poets, writing from within and not from a, mostly, external position. But perhaps more importantly, the discussion itself is in need of revision. The system described is essentially an old system, that is rapidly becoming defunct. Contemporary Flemish poetry is hard to fit into the categories that are distinguished by for example the Hotel New Flanders anthology – which put forward an essentially territorialized understanding of poetry (its rootedness in Flemish history), but also more metaphorically speaking, by confining poetry to its manifestation on the page, and disregarding the international influences that shape Flemish literature.

Contemporary Flemish poetry breaks with this logic. Poets like Maud Vanhauwaert (1987) and Lies van Gasse (1983) work across disciplines – visual arts, performance art and theater respectively – and others like Xavier Roelens (1976) and Tom Van de Voorde (1974) look towards international (especially American) rather than local traditions, as does Els Moors (1978). Emerging poets like Arno van Vlierberghe (1990) and Mathijs Tratsaert (1992) are highly conscious of the Flemish literary canon, but only use and transform it for their own goals. Literature is becoming a global practice: discussions on poetics have grown into an exchange. Precisely this communal, social aspect contributes to a growing liveliness across borders that would be wrong to suppress. But we have to admit: we will cover much less Flemish ground in this piece.

Similarly, Dutch poetry has been opening up. The old opposition between traditional and experimental, and between ‘accessible’ and ‘formalist’ or ‘conceptual’ poetry is starting to crumble. This started in the nineties, when poets actively began to cross the boundaries between anecdote and concept, between lyric voice and textuality that framed the debate for a long time. Typical poets that emerged in the nineties like Tonnus Oosterhoff (1953), Mustafa Stitou (1974), K. Michel (1958), Arjen Duinker (1956) and Astrid Lampe (1955) played an important role in this. We will refer back to these frames, even though we think they are faulty, because they are important for how poets self-identify, even if redefining and eventually displacing them is our main mission here, and Dutch poetry is far too eclectic to reduce to the terms of fossilized debates of the past.

So, this is not a literary history, or only partially; much more so it is an attempt to trace the past by exploring present developments, telling a story of shared affinities and not of epochal ruptures. A crowded photograph, with a shifting background, a montage perhaps. Sure, our views are biased, and can be thrown up for debate, but precisely this can help connect our situation with the situation elsewhere.

Off the page

One of the developments with a major impact on the direction of the literary landscape in the last few years, perhaps the last decade, is the shift towards poetry that moves outward – off the page, blurring the boundaries between text and performance.

This development takes many shapes, from what you could call “media poetry” to slam poetry, or crossovers with other disciplines and a more expanded view on poetry and its role in the public sphere (more on that in the second part of this piece). The perennial question of what constitutes literary value is revisited here, especially from the viewpoint of literature’s effect, rather than the question of what literature really, essentially is. We will come back to this point more often; it is one of the possible ways of displacing the static, overly formalist frames prevailing in literary discussions in the Low Countries since modernism.

Slam poetry can be seen as one of the fields in which this has played itself out. While Dutch slam poetry has never been programmatic in a very explicit sense, much less political, it can be seen as a cultural force with the power to pry open the literary field. The cultural debate itself had come to a standstill, just like the rest of Dutch society, probably because of economic prosperity and euphoria over the end of history. Politically speaking, the nineties saw a historic compromise between social-democrats and the liberals (of the conservative kind), resulting in an unprecedented wave of neoliberal reforms (in the housing market, the financial sector and many other domains of society).

Still, slam allowed new practices for poetry to come into being. Not so much through purely formal innovation – mostly, slam poets adhere to fairly traditional poetics in that respect – but by opening up the available environments for the reception and production of poetry. While slam embraced established forms, its critique of the text as an object of passive consumption and its endorsement of the dynamism of the stage was powerful. This “wave of democratization” introduced by slam poetry is not in any way new; one of the longstanding proponents of a poetry full of affect and intensity, a poetry that was to be performed, not read, was Simon Vinkenoog (1928-2009), active from the early fifties, one could call him a Dutch Beat poet (he promoted the work of Allen Ginsberg). He brought many acclaimed poets to the stage for the first time in the Netherlands in 1966, during a watershed event called “Poëzie in Carrré” (Poetry in Carré) and remained a great animator and organizer in the scene up to his death in 2009.

More recently, the gap between slam poetry and the traditional world of publishing has begun to close. Poetry slam now occupies a central position in literary culture, it has almost become an institution itself, with its own rules and rituals, like a tongue-in-cheek competitive atmosphere, recurring slam championships in many cities and a prestigious national championship every year in which the regional champions battle each other. While this was hailed as proof of the renewed popularity of poetry, it can also be argued – as it has indeed been argued – that slam’s institutionalization has consolidated the further privatization of poetry in recent years, turning the poem into an object of consumption yet again.

Erik Jan Harmens (1970) won the championship in 2004 and not long after published his first volume of poetry. His second volume of poetry bears a title that ironically and slightly ambiguously captures many slam poets’ self-understanding in an age of anxiety over self-performance, the media’s influence and authenticity: Underperformer. After Harmens, many more slam poets were offered publishing contracts, like Krijn Peter Hesselink (1976), Kira Wuck (1978), Daniël Vis (1988) and Ellen Deckwitz (1982). Nowadays, success as a performer heightens the prospect of being picked up by publishers, who see commercial potential in poets with a stage reputation. Mainstream commercial publishing houses still publish poetry, and slam poets usually do well.

An example is Ellen Deckwitz, who won the championship in 2010 and has become one of the most active members of the community. Her work combines a few very strong currents in contemporary Dutch poetry: ironic distancing, romantic longing and a sense of loss, also in the metaphysical sense of the word. Deckwitz’ second volume Hoi feest (Hey Party) opens with an instruction for a prayer:

Clasp your hands and try

to grasp the meanings that arise:

1a. praying (they wax),

1b. applause (they wane).

Make the above explode

and the hands form a path

between your wrists. Meanings break

arms. Wrists and hands form a suspension

bridge under collarbones. With your head above,

rocking and pulling your arms out of their sockets

until you can jump rope. That’s okay,

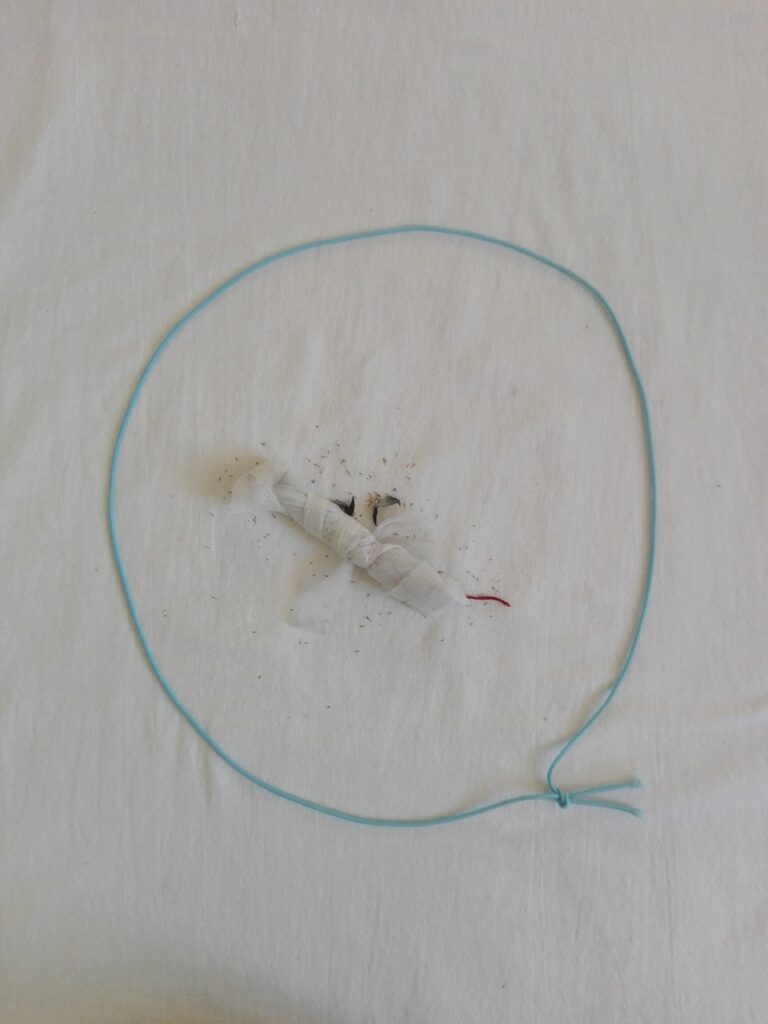

moving makes you live even longer. Throw this loop,

everything comes back to you. Span

above the others, make them a ravine

beneath your limbs. Let it

sink in: your arms are not a net

but just a bridge and does that reassure you.

Translation by Ellen Deckwitz (1)

(1) Unless noted otherwise, translations are our own.

This results in poetry that is attuned to the conditions of writing (the stage, where one’s fragile sense of being, especially in the presence of others, is heightened), while maintaining the hope of transparent communication and real contact.

Slam poetry often plays with this tension, typically in a romantic fashion. This indeed may be a characteristic of the many Dutch slam poets overall: romanticism, commitment to lyric self-expression, and a penchant for theatricality and affect. This particular combination of traits can be traced to a long list of poets, indicating the extent to which slam is a part of the mainstream of Dutch literature, on which it models itself, rather than setting itself consciously apart.

Among these poets are Menno Wigman (1966), a romantic poet par excellence, and Gerrit Komrij (1944-2012). Gerrit Komrij was a highly contradictory figure and intellectual, both as a prolific poet, controversial anthologist and a vigorous polemicist, whose tirades and often unscrupulous editorial choices had a paradigmatic impact on the Dutch literary canon; the way he, in his still seminal anthology De Nederlandse poëzie van de 19de en 20ste eeuw in 1000 en enige gedichten (Dutch Poetry of the 19th and 20th Century in 1000 and Some Poems) debunked the importance of the “Fiftiers”, a legendary, loosely knit group of modernist poets who shaped post-war Dutch poetry, shows Komrij at his most controversial. Saliantly, Komrij himself loved the formal innovation of the Oulipo writers and the experiments of someone like Alfred Jarry and others in pataphysics. It could be argued that Komrij, in a way, embodied a different idea of what a modernist poetics constituted, and cannot be written off as a purely conservative figure.

Komrij’s own poetry, with its parodical intent, wit, cannibalization of different styles and deft use of literary convention proved hard to classify at first – he was labeled as both a neo-romantic poet, an aestheticist and a formalist – and is known for its traditionalism and fixed forms. The poem ‘Desolation’ is a typical example:

Desolation

The following day refinds me in the maze.

I’m trapped inside for good. It’s now quite clear

I’m once more blinded by that figure’s gaze.

My mother, rising in a sacred sphere.

Amid such bustling traffic – would she still be there?

I dare not leave my alley-web. She looked

Just like a child, the girl of bygone years –

Her face so full of tenderness, yet spooked.

I see her dress still swirling, marble-slick.

This memory I’m most hard put to shelve:

Her right hand resting lightly on a stick,

She winked at me upon the stroke of twelve.

Translation by John Irons, courtesy of Poetry International.

By now his poetry may have become a model for many poets, both in slam and outside of it.

It is not hard to see how poets like Menno Wigman have borrowed from him:

(…) – Break every pen. Duff every letter up.

No tongue that can console,

no word blush rose at Kaspar and his doglike death.

Translation by John Irons, courtesy of Poetry International.

Experimental lineages (and their displacement)

Martijn Teerlinck (1987-2013) won the national poetry slam competition in 2010 – tied with Daan Doesborgh (1988). Teerlinck’s work testifies to the diversity and pluralism of the Dutch slam scene. The tone of voice of his work is exuberant and dark, archaic even, and has a mantra-like quality:

Dying is slowly changing into a word.

Dying is the most harmless thing there is.

There is a need for mortality because there is a need for convenience.

There is a need for poverty

poverty is not maternal

Poverty is not a child poverty dries your clothes

Poverty is fiction but at least it stands up straight when it’s called names

Poverty is used to death

Poverty can’t be touched

poverty moves slowly and cautiously

Like an illiterate

Every mythical illiterate can read his own history

Every mythical illiterate can decipher a funeral

Every mythical illiterate is eaten by the use of language

There is a need for a sphinx

To lay down before the use of language with puzzling calm

There is a need for a deciphering sphinx

To slowly take away our words with an answer

There is a need for a big gray sphinx

With a real and calm young skin

There is a need for a big gray metal sphinx

That reeks of our rooted poverty

There is a need for a sphinx with a living balm face

To model ourselves on

There is a need for a calculating war sphinx

To shelter us against something

There is a need for a sphinx with hunger

To eat us

There is a need for a fragment

Of a sphinx

He was known for his performance, which stood out in the world of Dutch slam for its intensity. With his alter ego The Child of Lov he stood on the verge of an international breakthrough. Sadly, he prematurely died in 2013. His posthumous works Ademgebed (Breath Prayer) came out in 2014.

Teerlinck’s work was clearly influenced by Lucebert, the most influential “experimental” and innovative poet of his generation, the Fiftiers. Lucebert (1924-1994), a pseudonym combing the Italian word for light luce with the Old-German bert or brecht, meaning ‘light or light-giving light’. The fragment from his following, well-known poem “I seek in poetic fashion” beautifully captures his disjunctive syntax and experimental style, and its derailing of the senses:

(…)

in this age what people used to call

beauty beauty her face has burnt

she comforts mankind no longer

she comforts the larvae the reptiles the rats

but she startles mankind

and strikes him with the sense

of being a breadcrumb on the skirt of the universe

Translation by Diane Butterman.

The imagery in this poem speaks to Lucebert’s bleak post-war vision, in which the aesthetic comforts and complacencies of the past had become totally compromised. Experimentalism here also implies the breakdown of traditional society. As a member of the international COBRA movement, Lucebert was also involved in the arts of his time.

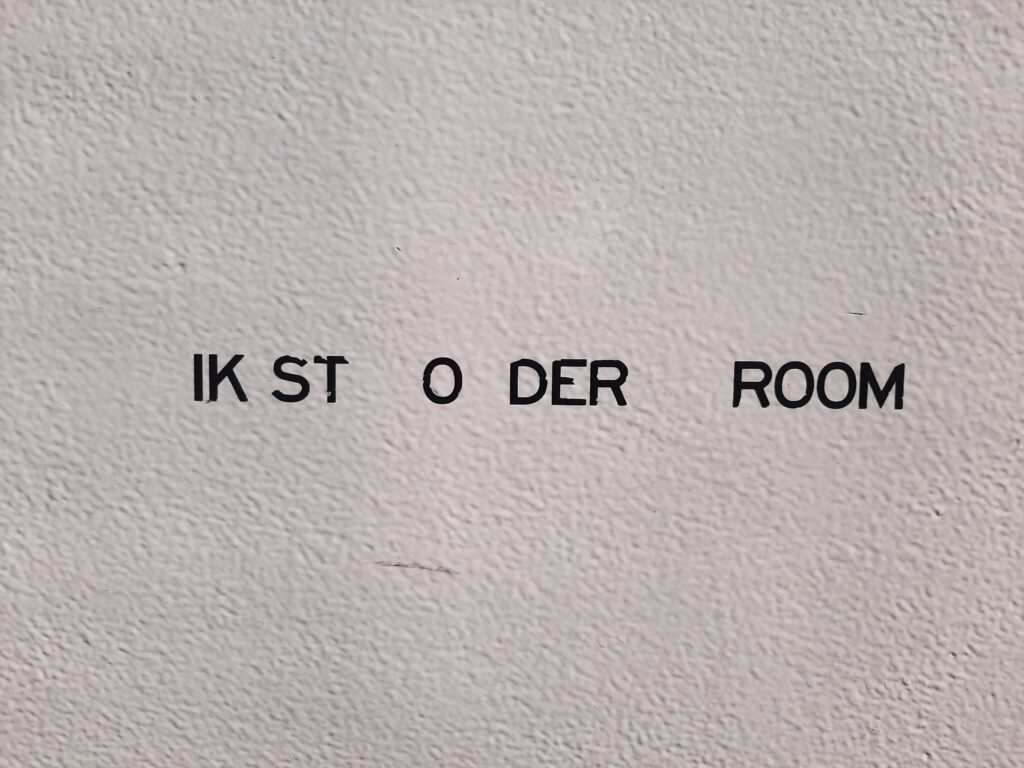

Together with Gerrit Kouwenaar (1922-2014), another Fiftier, Lucebert can be credited for paving the way for a fully-fledged modernism in Dutch poetics. The influence of Gerrit Kouwenaar has been as considerable as Lucebert’s. His dense lines, circling around nothingness and death, in which archetypal motives like “house”, “flesh”, “room” figure, contributed massively to the idea of poetry as self-enclosed, autonomous artifact. This is mostly an academic construct; the poetry of Lucebert and Kouwenaar, through the reading methods developed by New Criticism, taught a whole generation of literary critics “how to read poetry” and made anti-mimetic reading habits the norm.

Ever since, the empty line, the white surrounding the poem, has become a bearer of meaning, if not the central signifying element of the poem, a tendency that has become very visible in the reception of the work of Hans Faverey (1938-1990). It was this “purified” poetry that the Maximal Poets, early representatives of a postmodern strain in Dutch literature, so vehemently opposed. Poetry, for them, was to be impure, realist, embrace the world instead of retreating from it. But in fact, a more accurate – and productive – assessment would be to understand this poetics as one of an unresolved tension between the mimetic and anti-mimetic, as in many of Faverey’s poems, and as the latest volume by Kouwenaar, Totaal witte kamer (Totally White Room, 2002), aptly illustrates:

TOTALLY WHITE ROOM

Let’s make the room white one more time

one more time the totally white room, you, me

it won’t save time, but one more time

make the room white, now, never again later

almost echoing perfection

our lines more white than legible

so one more time that room, once and for all total

the way we lay there, lie, shall lie there

more white than, together –

Translation by Lloyd Haft, courtesy of Poetry International.

The Fiftiers became key figures in what, up to the end of the eighties, had become the central dichotomy in Dutch poetics – the opposition of so-called experimental, language-driven hermeticism and confessional, (neo-)romantic, accessible, in short “normal” poetry, dealing with life and all things human. As the foremost poet of his generation Lucebert was, for a time, the father of all future poets with a penchant for derailing metaphors and the associative sequence, such as the inimitable Tonnus Oosterhoff (1953) and the solemn H.H. Ter Balkt (1938). The Fiftiers became an influential model, both positively and negatively, that reinforced the idea of generational rupture as a structuring element in Dutch literary history. The Sixtiers, for example, as their name implies, presented themselves as antithetical to the Fiftiers. One of their magazines Gard Sivik showed a road sign, indicating the Fiftiers’ era ended with them.

The theoretician of the Fiftiers, Paul Rodenko, publicized the same view in anthologies such as Met twee maten (With Two Measures). But in the nineties, co-existence and pluralism supplanted conflict and dualism. Two measures became many measures, and numerous ways of measuring. By then, Lucebert had become normalized, a canonical figure; one of his lines (‘Everything of worth is defenceless’) even made it into a neon sign on the of building of an insurance company in Rotterdam. The experimental/innovative versus normal/traditional axis has long dictated the Dutch debate but has now largely been displaced, even though people still use it to frame contemporary poetry.

The anxiety of Lucebert’s influence, the popular discourse of epigonism and the demand for originality have always played an important role in young poets’ definitions of self, but newer generations seem to have broken the cycle. For the young poet Martijn den Ouden (1983), Lucebert clearly is an important figure, as well as Bert Schierbeek (1918-1996), a lesser known but equally fascinating Fiftier, who started his career with experimental novels in a high modernist style, and later reverted to sparse lyric poetry with almost no metaphors. Den Ouden seems to have appropriated both the exuberance and the economic in the Fiftiers’ lineage. His poetry is reminiscent of their writing for its sound-driven, nonsensical style, but he seems to have no interest in proclaiming anything – something that tends to result in banality – using Lucebert as a mere prop. In dealing with these experimental modes, Den Ouden is far more relaxed, even playful. His exuberant, sometimes mythological tone of voice is always accompanied by a more down-to-earth, ironic style and the use of almost naive and plain statements:

in this darkness I feel ferns under my feet

twigs

loose soil

grass

asphalt concrete

grass

a metal fence

grass

asphalt concrete

grass

loose soil

twigs

ferns

I have never – eyes closed and barefoot – crossed a road

like this

This formal eclecticism, ranging from (pseudo-)ready-mades to incantations, combined with a sense of parody, resists a reading that would demarcate poetry as normal or experimental (or “normalized experimental”, for that matter) modes of writing. This goes to show how Den Ouden upsets expectations. There is an element of satire and often wry critique in this; Den Ouden is fond of reversing the normalized social order and its policing of the boundaries between animal and human, reason and madness, order and chaos.

The banal, the formal and the lullig

Another influence on Den Ouden’s work is the writer and poet Gerard Reve (1923-2006). Reve is a very influential figure in Dutch culture and society. He is commonly known as one of the so-called “big three”, who dominated the cultural field after World War II; the others being Harry Mulisch (1927-2010) and Willem Frederik Hermans (1921-1995). The work of these writers reflects the impact of the Second World War on Dutch society, often unsettling the comfortable black and white morality and meditating on questions of guilt and complicity.

Reve’s writing is also highly reflective of social changes in the sixties. He openly talks about his homosexuality and a recent biography quite rightly stressed his active role in gay emancipation. The themes of secularization and depillorization – the process in which the formalized social segregation that characterized Dutch society for most of the twentieth century, resulting in the pacification of political conflict, was torn down – play a major role in his work. He was raised by active communists, and later converted to Catholicism. He interestingly identified himself as ‘the people’s writer’, a nom de plume journalists readily adopted and still use when Reve is discussed. Reve often stressed that he simply wrote novels about love and God for ordinary people and detested intellectualism.

Although Reve is famous for his novels, like De Avonden (The Evenings), Op weg naar het einde (On My Way to the End) en Nader tot U (Nearer to Thee), his relatively small body of poems has had a great influence on Dutch poetry. He invented a wrought ironic style that resembles his prose, in which the sacred and the profane, the formal and banal all interact and collide. A clear example can be found in the poem “A New Easter Song”, from the story collection Nader tot U, that also contains a poetry section, called “Spiritual Songs”:

Not having been drinking, I praise God.

I’ve seen lots of things today.

Strolling about in the lower town,

contemplating the Last Things,

I saw a boy, presumably a German tourist,

and followed him, thinking:

I will spank your ass, or if there’s no chance,

you’ll just hit me,

keeping busy is the main concern – (…)

A great poet like Kees Ouwens (1944-2004) was heavily influenced by Gerard Reve. In his first publications, like the poem “I get older”, the voice of Reve can be heard:

I get older

and that, in itself, is hardly surprising.

But when I lie down on a canapé,

that is not my own,

taking a cigarette from an expensive ivory box, that doesn’t

suit me,

I realize that I have wasted a lot of time

and that the future will be just the same

even if I can not see that

Critics have made a distinction between the early and a later Ouwens, the early one writing in this “Revian” decadent, romantic-realist, confessional style and the latter, producing difficult, hermetic texts that peer into the abyss of language. Although it can’t be denied that there are stylistic differences between the early and later work of Kees Ouwens, the play between formality and irony has remained a powerful aspect of his writing throughout.

Martijn den Ouden must love Reve’s wry sense of humor, his mix of aggression, vulgarity, corny jokes and sentimentality, but also the sudden tenderness of his lines. It’s not hard to see that other young, but quite different poets like Daniël Vis, Flemish poet Maarten Inghels (1988) and Hannah van Binsbergen (1993), an emerging young Dutch poet, have read and digested Gerard Reve. Inghels and Van Binsbergen’s work, for instance, shows a fondness for archaically sounding, ceremonial language and incantatory repetition, and Vis’s tone is dry, comical in a dark, “Revian” way. It is telling, and a remarkable fact that Reve’s heritage is still so alive and recognizable.

Another interesting aspect of this heritage is something the Dutch would refer to as “lulligheid” – a virtually untranslatable term, rivaling gezellig as quintessentially Dutch, in the way it tries to capture a sensibility of comical failure. While on the level of everyday use, the term might mean both something like nasty, imbued with pity, and something downright negative and judgmental, like stupid, it has also entered cultural discourse as a sublimation of these two meanings. This lulligheid is a way of perceiving life, a poetics of the everyday, characterized by its depiction of human activity as clumsy, futile and tragicomic, but never dramatic, anti-dramatic even.

Reve’s work is suffused with lulligheid, and many other Dutch artists have absorbed this. The best example is perhaps the ur-Holland depicted in Van Warmerdam’s films and screenplays. Here is a clip from De Noorderlingen, a film on domestic dysphoria in a desolate suburban setting. The absurdist, dark and ominous quality of his work is enhanced by the lullige atmosphere.

In prose, perhaps the genre that is most prone to lulligheid, we could name Simon Carmiggelt, Maarten Biesheuvel, Arnon Grunberg, Herman Brusselmans, Tom Lanoye and Anton Valens. In poetry, in addition to the poets we listed above, it can be found in the work of Ingmar Heytze, Mustafa Stitou and Bernard Wesseling.

Exploded views

The idea of experimentation is not limited to the page, or to the traditions that started with the Fiftiers. Maartje Smits (1986) is almost a poet in disguise: her work is as much in video, text as it is web-based. A graduate of the Rietveld Academy’s program Beeld en Taal (Image and Language), that brings the practice of writing in close contact with the fine arts and performance arts, she represents another type of poet, one that works in proximity to other media and disciplines, often unburdened by the clichés surrounding traditional poetic discourse. The Rietveld Program, while not exactly a creative writing program, has produced many gifted poets over the last few years; Martijn den Ouden is one of their graduates as well. Smits creates multilinguistic poems and video’s, part reportage, part poem. She self-identified as a private investigator once, and she often infiltrates in environments where she looks for a sense of intimacy. In “Via”, the video below, Smits is seen at a closed down gas station on a busy road, holding up signs. The voice-over recounts a memory from the past, making a list of questions for a mother ending with the question “if she could pick her up”:

Bernke Klein Zandvoort (1987) is another Rietveld graduate, and there are some affinities between her and the work of Smits. At first, it is easy to mistake her work for a poetry of poignant observation, or lyric impressionism. But language is material for her, something to work with, not an expressive medium in itself. Reality is always caught in the process of coming into being:

at my table in a square filled with tables

the sunshades run together, islands of spilt milk

pressed towards each other with a fingertip

the sun falls sifted through the mesh

there is patient smoking

the body a baggy sweater in a bucket seat, puffing

as my dad calls it at the back of my mind

an accordion player shuffles between the tables

with a smile dredged through the varnish

if ah’ve said ah’m no here

then ah amna here

a man addresses his telephone

I call home to say I am in Venlo

and imagine how at the other end

the terrace, the salad with croutons and the tinny snippets

of accordion are put together

and whether space is being left

for the girl with her laces tied red-white-blue

for the little dog that looks round semi-exuberantly

while it kicks out the square from beneath it

Translation by Willem Groenewegen, courtesy of deBuren

The first lines (“at my table in a square filled with tables / the sunshades run together”) are typical; Klein Zandvoort once compared her poetry to an exploded view, a picture, as for example in a manual, where different parts are shown in their “virtual” state, not yet integrated. For this reason, there is an almost ghostlike and mildly disorienting quality to her work – something that puts her in proximity to Smits’ work and Annemieke Gerrist (1980), another graduate of the Rietveld program whose work has been called photographic. We can also think of poets such as F. van Dixhoorn (1947) and Astrid Lampe (1955), who share her “architectural” view of the page as a multidimensional structure and use fragmented language.

Animation The sun in the pan

Translated by Astrid Alben.

To be continued